During one of auto racing’s most dangerous eras, there was one exceedingly deadly year in which 100 spectators and a half dozen drivers, some of them racing icons, perished.

In today’s world, motorsports wouldn’t have survived. It almost didn’t then.

The year racing nearly died was 1955.

During a violent four-month stretch, one tragic event piled right on the heels of another, with the catastrophes increasing in magnitude until they climaxed in a thundering crescendo of disaster on June 11 during the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

These events not only assaulted the sensibilities of racing’s followers, but those of people who understood little about the sport as well. That resulted in a big problem.

It all began on March 17 when Larry Crockett, the 1954 Indianapolis 500 rookie of the year, died during a sprint car race at Pennsylvania’s Langhorne Speedway. While tragic, Crockett’s death barely jolted the shock needle. Sprint car drivers died routinely in those days.

On May 1, however, death claimed another sprint car driver at the same track and people began to take notice. Ironically, tough guy Mike Nazaruk died while leading the Larry Crockett memorial race.

Two weeks later, Manny Ayulo, son of a Peruvian diplomat, crashed brutally in turn one at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Pulled from his crushed car alive, he died the next day.

On May 26, word arrived at the speedway that 1952 Indianapolis starter and two-time world champion Alberto Ascari died testing at the legendary Monza circuit.

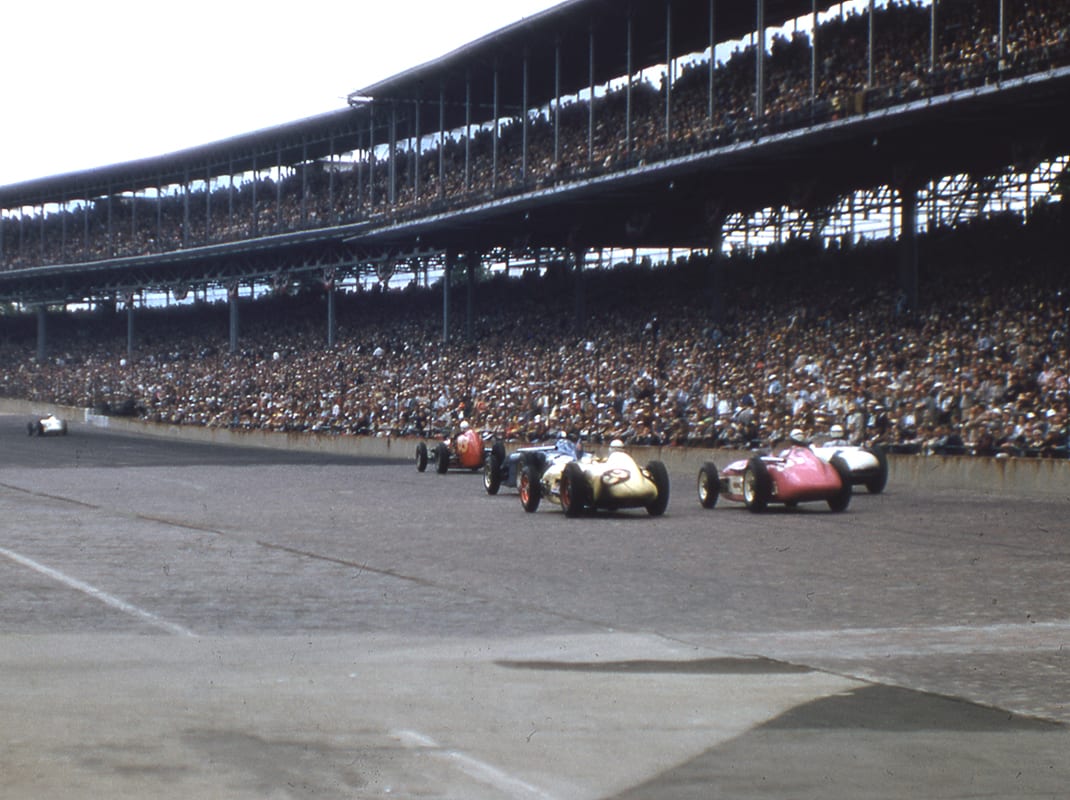

As disturbing as these multiple deaths were, however, they were but a harbinger of the epic tragedy set to unfold on race day at Indianapolis. After a stunning duel with Jack McGrath, Bill Vukovich appeared on his way to his third consecutive Indianapolis victory.

As Vukovich hauled down the backstretch on his 57th lap, a multi-car accident unfolded in front of him. He nearly cleared it but, in a split second, Al Keller pushed Johnny Boyd in front of him. Vukovich rode over Boyd’s wheel, catapulted high into the air and cleared the fence. Flipping end over end, Vukovich’s car hit a jeep, a car and a pickup truck before smashing to the ground upside down and in flames.

The driver considered one of the best ever was dead.

Vukovich’s renown had already transcended auto racing and crossed over into pop culture. The impact of his death was enormous. It was inconceivable that a personality of his stature could, in the words of some critics, “…be sacrificed for a sport.”

The story made front pages around the world.

Editorials decried auto racing as a waste of human life and clamored for a ban. Several state legislatures picked up that challenge and bills were proposed accordingly. Even the young evangelist Billy Graham, preached against auto racing and its human carnage.

As the talk of legislative action dragged on, Vukovich’s longtime car owner, California billionaire oil man Howard Keck, acted. He shut down his racing operation.

“‘Vuky’ wasn’t driving for Keck that year,” explained Vukovich’s team manager Jim Travers. “But he was worried about the liabilities involved, for any car owner, had ‘Vuky’ gotten over the fence on the frontstretch like he did on the backstretch. The death toll could’ve been astronomical. One day I got a call. Keck told me to turn off the lights and lock the shop. He was done racing. The liabilities weren’t worth it.”

More critical to the state of American auto racing than one car owner withdrawing, however, was the unrest among AAA executives. They questioned the morality of being leaders in automotive safety, while sanctioning a sport that killed routinely.

Click below to keep reading.