While Tony Hulman labored to resurrect Indianapolis Motor Speedway from the ravages of neglect incurred during World War II, a new track took shape within sight of Hulman’s racing empire.

Directly across 16th Street from the speedway’s second turn, on property that once served as a football field for local high schools, sprang the deceptively, but cleverly, named Indianapolis Speedway.

Intended to take advantage of the popularity of midget racing, the facility was the brainstorm of one of those larger- than-life characters that seem drawn to auto racing.

Randall Wayne “Rags” Mitchell, born in the American Beauty food-canning company town of Austin, Ind., was an imposing 300-pound giant with a personality to match.

Working out of his office in a room at the Claypool Hotel in downtown Indianapolis, Mitchell dressed in silk suits, donned diamond cuff links and drove new Cadillacs, which he readily loaned to drivers in town to race.

Mitchell cultivated a well-situated relationship with local politicians that enabled him to acquire many lucrative liquor permits, the foundation of his substantial financial holdings. He operated a Falstaff beer distributorship called Friendly Beverages and held investments in at least two other watering holes, Mitchell’s Tavern and the colorfully named Tic Toc Tavern, which is still in operation at 2602 E. 10th Street.

Purpose-built for midget racing, Mitchell didn’t break ground on the quarter-mile paved oval until March 1946.

Still, he managed to beat Hulman to the finish line for 1946 Indianapolis racing activity when he staged his first race the night before Hulman’s first 500. More than 20,000 fans reportedly competed for room in the 6,500-seat grandstand to watch double features that were won by Leroy Warriner and Ben Emrick.

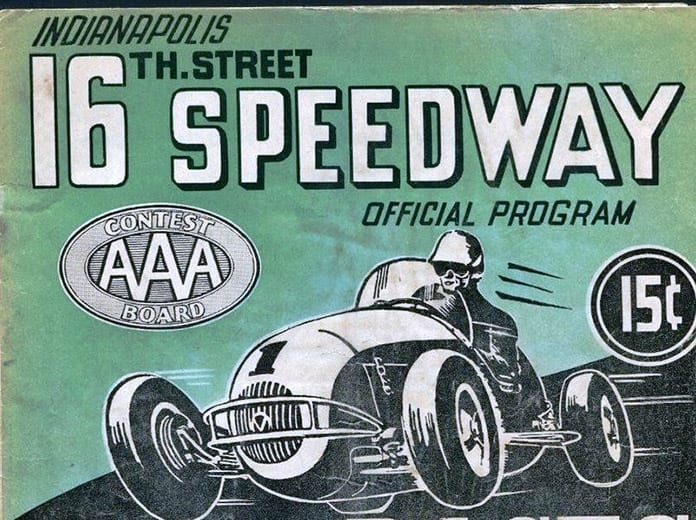

Hulman gave Mitchell his comeuppance, however, when the original Indianapolis Speedway’s bevy of lawyers suggested it would be judicious to change his track’s name. And while he often alternated the name through the years, the one Mitchell initially chose, and the one that’s remembered, was 16th Street Speedway.

While hundreds of races ran there during its 13-year history, 64 in 1946 alone, the mainstay of 16th Street became the Night Before the 500 midget races.

Often double and tripleheaders, the events ran from early afternoon until the wee hours of the morning. Bill Vukovich, Troy Ruttman, Eddie Sachs, A.J. Foyt, Len Sutton, Jack McGrath, Shorty Templeman, Mike Nazaruk, Art Cross and Johnnie Parsons are but a few who competed and then ran the 500 the following day.

Duke Nalon once explained to the Indianapolis Times what it was like to race the Night Before the 500 and the Indy 500.

“In 1947, I was living in the Antlers Hotel and I got home at a quarter of four in the morning,” Nalon said. “I raced the same day at the speedway. I was driving the German Mercedes at the time and was exhausted even though I fell out early.

“But we all did it,” Nalon added, “because that midget racing at 16th paid the hotel bill every year.”

Foyt first raced in the Night Before the 500 in 1956, the last year for the tripleheaders. Years later he recalled the chaotic night to author Bill Neely. “The only problem with that was that the fans who were still there for the late race were so drunk they wouldn’t have known the difference between A. J. Foyt and Harley-Davidson,” said Foyt. “I placed fourth in the first heat race and 13th in the late-night show. And I won $68. Shorty Templeman swept the card.”

After Templeman scored the hat trick in 1956, Mitchell reduced the Night Before the 500 extravaganzas to doubleheaders for the next two years, with Gene Force and Tony Bonadies winning the final features in 1958.

The popularity of midget racing had waned and to compensate for lost revenue from reduced crowds, Mitchell, ever the showman/entrepreneur, produced a multitude of crowd-appealing shows.

He promoted jalopy racing, powder puff racing, street roadster racing, auto thrill shows, something called steeplechase racing and big-time wrestling. Anticipating betting being legalized in Indiana, he staged greyhound races.

Mitchell’s political contacts proved correct. A bill to approve pari-mutuel betting passed through the legislature but it never got off the Governor’s desk. Still, the two years of dog racing were quite the spectacle with the muzzled animals paraded out amidst canned music and in the company of a line of glamour girls.

Eddie Johnson won the last midget race there on Aug. 16, 1958, and Mitchell discontinued racing for 1959. A strip mall grew up on the site. Today, the complex is home to IndyCar’s headquarters.