Buddy Parrott, a former winning crew chief, told a story years ago about buying the buckshot at a local gun shop.

“He (the owner of the store) asked me about it one time,” Parrott said in the American Racing Classics book series. “He said, ‘You have a lot of hunters over there.’ I told him, ‘Yeah, we hunt about 40 (race cars) every Sunday.’”

It is unclear how many times Bertha carried buckshot. It is believed the last use of buckshot inside Bertha’s frame rails came Aug. 26, 1878, at Bristol (Tenn.) Motor Speedway during what was the track’s first night race. NASCAR didn’t weigh cars after races in those days, but began rolling them over scales after the Southern 500 at Darlington (S.C.) Raceway the following week.

At Bristol, a good bit of the buckshot came out during an early race pit stop. When windshields of the cars behind Waltrip began to crack, uproar ensued and many called for Bill Gazaway, NASCAR’s competition director, to find the culprit.

Bertha was impounded after a rival crew tipped NASCAR officials to the issue. DiGard crew members stood by sweating out the inspection process for a couple of hours but were finally cleared to leave. When a NASCAR official placed a jack on the jack pin to look under the car, crew members knew they were in the clear, as that was the exit path where the buckshot flowed out.

“When they took our car, I thought we had been caught,” said Gary Nelson, then crew chief for the team. “But once they jacked it up, I knew we were home free. The jack was hiding the one place where we dumped it. They were convinced they had found the culprit. They couldn’t find anything and they told us we could go.”

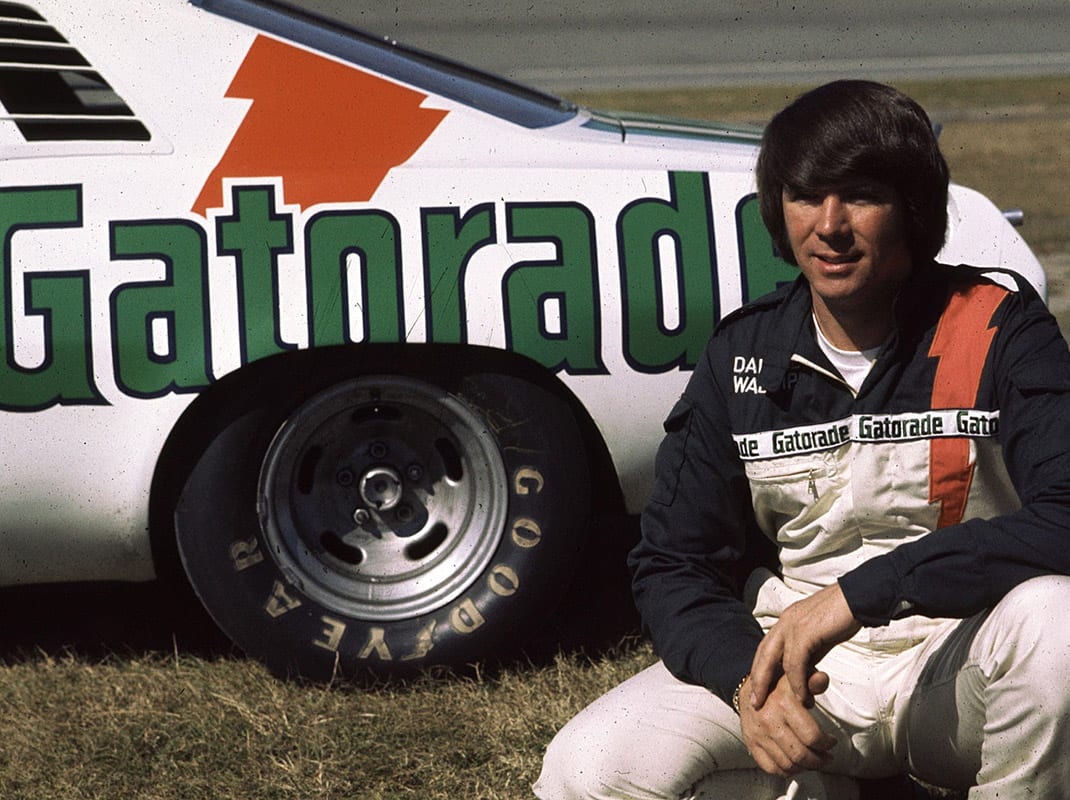

Waltrip remembers an incident that initially fueled teams to find creative ways to circumvent the rules during an era when the inspection process was very different than it is today.

“Kind of what shaped this situation in those days was a Sunday morning at Martinsville Speedway,” Waltrip said. “We were in the drivers’ meeting and I asked Bill Gazaway why they didn’t weigh the cars after the race? He absolutely jumped down my throat and said, ‘When my cars … they were always his cars … when my cars go on the line ready to start this race, they are legal. So there’s nothing on those cars that would happen during the race that I would need to check after the race. Do you understand me?’ I said, ‘Yes sir. I understand perfectly.’

“People thought if that’s the way you’re going to be, then here’s what we can do. They had grain scales back then, not the sophisticated scales they have today,” Waltrip continued. “We would run our car across them before the race and then go race. You knew if they loaded up the scales and all of the inspection tools while we were out there racing, you knew they weren’t going to check anything after the race. They kind of dictated when, where and what you did during the race based on what they did before the race.”

After the Bristol incident, Bertha was pretty much put in the corner and covered, destined to become a show car. When NASCAR made the decision to follow Detroit’s lead and utilize race cars with smaller wheelbases in 1981, Bertha was purchased from DiGard Racing and was displayed at the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in Talladega, Ala., for many years. Today, Bertha is featured in the NASCAR Hall of Fame in Charlotte, N.C.

“By the time we stopped using Bertha, she was pretty banged up,” Waltrip said. “We discarded her several times but each time something would happen, we would pull her out, dust her off and she would go out and win again. We would push her out of the way and say, ‘She’s done.’ Then we’d go back and get her. In the end, I think she was pretty happy to hear she was going to rest in a museum someplace.”