Editor’s Note: NASCAR is celebrating its 75th anniversary in 2023. SPEED SPORT was founded in 1934 and was already on its way to becoming America’s Motorsports Authority when NASCAR was formed. As a result, we will bring you Part 10 of a 75-part series on the history of NASCAR as told in the pages of National Speed Sport News and SPEED SPORT Magazine.

The Automobile Manufacturers’ Ass’n’s involvement in NASCAR accelerated in 1956 as Ford, Chevrolet and Pontiac fielded factory-backed teams and Chrysler experienced a sales boom in part because of the Kiekhaefer team’s success with its 300 model.

The AMA accepted a high level of involvement despite questions about the safety of NASCAR and motor racing in general, which resurfaced in May when 16 people died during the Mille Miglia road race in Italy, because the public seemed to possess an insatiable love for fast, powerful cars on the track and in their driveways.

However, even as Detroit and NASCAR prospered, the relationship screeched to a halt in 1957.

On June 6 the AMA “voted to halt participation of its members in racing and place the emphasis in its future advertising on safety,” reported the June 12 edition of NSSN. The decision left factory-team members at a loss.

“I’m going back to California to look for a job. The drivers now have all the cars and what few parts we had,” said Chuck Daigh of the Chevrolet team.

Ford team member John Holman deadpanned, “I’m in the process of closing up the shop. The cars are now in the hands of the drivers.”

NASCAR, at least in public statements, seemed unaffected by the AMA pullout: “The apparent divorce of the auto industry from racing and other tests of speed occasioned no particular stir,” stated the terse response. NASCAR officials expected “little or no effect on the general alignment of cars and drivers for 1957 (and) the so-called factory drivers were expected to continue on an independent basis, undoubtedly in their same cars.”

Notwithstanding the drawbacks for factory-team members, NSSN commented on the benefits of the forced move away from big-money teams: “The factory-scored teams cut a broad swath through the racing ranks (discouraging) the independent drivers because of their substantial financing and the use of what was termed ‘optional equipment.’”

Such equipment, including fuel injection and superchargers, was disallowed by NASCAR in April in favor of normal production four-barrel carburetors, in part, because Ford and Chevrolet violated NASCAR’s new “Pure Advertising Law.”

This policy took Ford’s Daytona Beach manufacturer points away because Ford advertised its successes during Speedweeks as official before they were deemed official by NASCAR. Chevrolet lost its manufacturer points from a 1-2-3 sweep in Hillsboro, N.C., on March 24, for failing “to advertise the horsepower ratings or the type of optional equipment used,” reported the April 3 NSSN.

Well-Financed Teams Exit, NASCAR Becomes ‘Sports Affair’ Once Again

As he negotiated sometimes-rocky terrain with the manufacturer-backed teams, Bill France held firm in his belief that the NASCAR Grand National circuit should feature stock cars altered only for the drivers’ safety.

After the AMA departed from racing, he said the absence of factory participation would put racing “back as more of a sports affair than it has been since the entrance of manufacturers into the field.”

That is, with the exit of well-financed, multiple car teams from NASCAR Grand National competition, driving ability and desire returned as the most important ingredient possessed by a driver rather than how craftily his car was engineered by a factory team.

Six weeks later, in the July 17 issue of NSSN, columnist Jack Senn assessed the post-factory-team changes on the Grand National circuit: “Everyone is working harder and this includes the top-notch drivers (who) are back working on their own cars and worrying with the rest instead of being flown in, handed their gloves, stepping into a finely-tuned automobile, then flying out again as soon as the prize money was collected.”

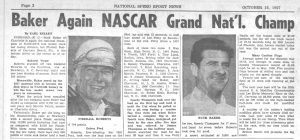

Despite the loss of team support, Elzie “Buck” Baker again garnered the most prize money en route to his second consecutive Grand National title. The tenacious defending champ trailed California driver Marvin Panch early in NASCAR’s long campaign, but by driving well throughout the season, he became the first driver to capture two Grand National titles in a row.

On the year, Baker won 10 of his 40 starts.

In his final victory of the year in Greensboro, N.C., Baker, who had already secured the season crown, was so determined to race he replaced his blown Chevrolet 300C transmission with one from a Chevrolet panel truck in time to start. His 38 top-10 finishes earned him $30,764 in season-long prize money.

While Baker’s record 10,716 points outdistanced sixth-place Glenn “Fireball” Roberts by more than 2,400, Roberts paced more races than any other driver. Voted the most popular driver, he led 16 races and 1,107 laps. In his 42 starts, Roberts won eight times and finished second on six occasions, serving notice he was a driver to be reckoned with in the future.

Prize Money, Competition And Honor

Several corporations bet on NASCAR’s future with agreements to award prize money at most NASCAR events. Already a fixture at the Daytona Beach race, Pure Oil added prize money at major races for drivers using Pure Oil and gasoline in their cars.

Another Daytona Beach sponsor, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., went even further in its sales war with Firestone and offered contingency awards in most of the 53 Grand National races to the top-three finishers who competed on its tires. These companies joined other Daytona Beach corporate participants Champion, Plymouth, Mechanix Illustrated, Sports Illustrated, Pepsi-Cola, Pur-0-Lator and Firestone as business partners with NASCAR.

When action concluded in NASCAR’s six other divisions, Jim Reed reigned in the short track division for the fifth straight year, while garnering three top-10 finishes in six Grand National starts. Bob Welborn won the convertible division title again and Ned Jarrett was the sportsman champ.

In the modified ranks, Ken Maniott emerged as the season champ. In the midget and sports car divisions, there were twin championships with Bob Harkey and Jim Whitman sweeping the midget laurels and Bob Ellis and Charles Bettmann taking the sports car honors.

As the racing season closed, the construction of the Daytona Int’l Speedway was just beginning, with ground being broken on Nov. 5 for the track that was scheduled to host its first event on Feb. 22, 1959.