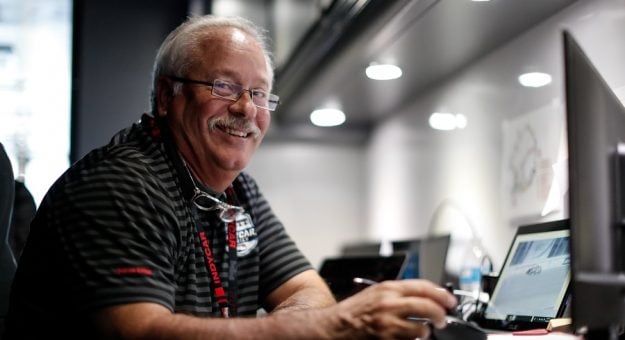

INDIANAPOLIS – Dr. Terry Trammell has been one of the most important figures in safety and innovation at the Indianapolis 500 since the famed orthopedic surgeon began his career at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in the early 1980s.

But it’s a career that almost didn’t begin.

The first time Trammell arrived at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, he was stationed at an infield care center out in Turn 3, where he tended to “drunks and sunburn victims” the entire day.

“There was also the police officer that got hit by a motorcyclist, and the motorcyclist that hit him,” Trammell recalled. “But that was the extent of it. I was a medical student from Indiana University and after that day, I didn’t wasn’t really interested in coming back if that’s all I was going to do.”

Luckily for the motorsports world, and other people who have had Dr. Trammell perform surgery on them, he returned and ultimately became one of the great safety innovators in auto racing history.

Trammell’s impressive career, which continues today in the field of bioengineering with IndyCar, was rewarded on May 21 with the 55th annual Louis Schwitzer Award presented by the Society of Automotive Engineers and BorgWarner Corporation.

“I’m from a motorsports family,” Trammell told SPEED SPORT. “My father worked for Perfect Circle. They sponsored dirt cars a lot. When I was a kid, we went to dirt car races. I was at the Hoosiers 100 before they had fences. You could just stand wherever. If nobody told you to move, you stood there. We all stood outside the fourth turn. It was a badge of honor to see who had the biggest bruise from the dirt clods coming off the track. You know how that would work these days.

“I’d been here as a spectator a couple of times when I was hardly tall enough to see over the people standing in front of me. I liked the sport. I listened to every 500 from the time I was in grade school practically and could tell you the names of all the guys in the corners that were doing the broadcasts.”

When Trammell got out of medical school and was less-than-impressed working on the drunks and sunburn victims way out in Turn 3 in an infield tent that looked more like a M*A*S*H unit than a hospital, he returned to IMS in a most unusual way.

“I lived next door to one of the photographers that was here all the time, Don Blake,” Trammell recalled. “Don would bring me along; I’d carry his bag. Every now and then I’d take a few pictures. I have the one picture I sold, got five bucks for it. I still have the $5 in a frame in my office as home. That was my career as a professional photographer, which was what I was supposed to be doing in 1981.

“I didn’t know that I was going to be the trauma doctor that day. I didn’t read the fine print in my contract. But I ended up being there when Dan Ongais crashed.”

Ongais’ crash in turn three was so severe, both legs were badly broken with compound fractures.

“The conventional wisdom at the time, it was a not soluble problem, treated by amputation,” Trammell recalled. “Fortunately, I was mulling over this. I wasn’t going to amputate it. It would turn black before I was going to take it off. There was a cardiovascular surgeon that did three tours in Vietnam. He walked by and goes, ‘Do you need help with that?’ I said, ‘He has a dysvascular extremity?’ He goes, ‘That’s no big deal. Let’s take care of that.’

“In the operating room he said, ‘You fix it so that the leg doesn’t move, I’ll fix the vessel, he’ll be fine.’ I wouldn’t call it fine, but he walks on it. I thought I’d get an opportunity to straighten it out better at some point down the road. He liked it just fine the way it was.

“It’s not pretty, but it works.”

In those days, there used to be big crashes nearly every day of practice. The SAFER Barrier was two decades away, and crashes were against concrete walls. It was almost common to see drivers airlifted by medical helicopter out of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for further treatment at IU Health Methodist Hospital.

The only driver so far in 2021 that has had to take a trip to the hospital was Santino Ferrucci, after he crashed in practice last week. Ferrucci was treated and released without injury and able to return to his race car the following day.

A big reason for that is the continued advancement in safety by IndyCar with some of the innovation created by Dr. Trammell.

“I stopped operating at the end of 2012 for a variety of reasons,” Trammell said. “That was the right time. I was at what I felt was the apex of my career, wasn’t anywhere to go from there. My interests had changed from being in the repair business to now I’m in the prevention business. So, if somebody gets hurt, I take it very personally because the means that we didn’t prevent the injury, something we overlooked, underestimated or whatever.

“That’s what we do now. Every accident is investigated not only from the standpoint of did it cause an injury but what worked that prevented an injury.

“If you want to see the best example of how these cars can protect the driver, go look at the first lap of the second race at Texas. There were seven cars involved, six that were disabled, that got hit multiple times. One car got hit once, the car that got through, the 48 car just had a little wing damage. Everybody else, it was like bumper cars. One of the cars got hit by the same car twice at the beginning and the end of the accident. How many different ways?

“If you looked at the degree of destruction of the car and the fact that we had one driver that had a bruised knuckle, another one that had a sore knee, a little muscle strain from being spun around like a top several times, it was perfectly understandable. Yeah, that happens.

“They worked. Do they always work? No. But we’d like to think they would always work.”